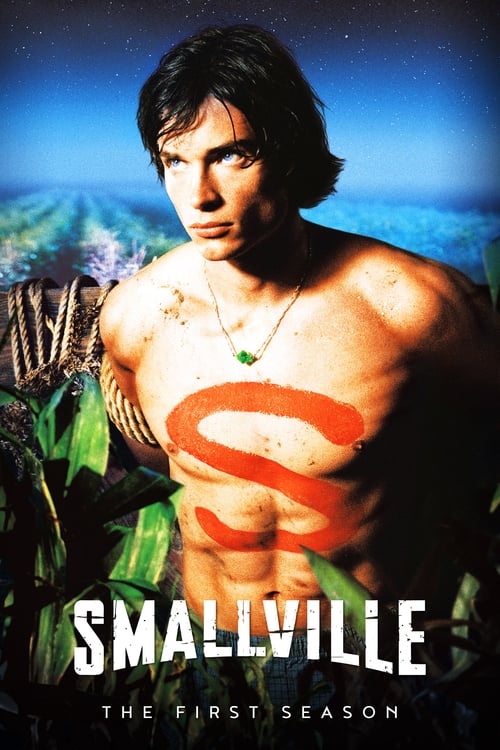

When Smallville premiered on October 16, 2001, nobody could have predicted it would fundamentally reshape how television audiences understood the superhero origin story. What started as The WB’s ambitious gamble—a 43-minute weekly journey through Clark Kent’s transformation into Superman—became something far more significant: a cultural touchstone that ran for ten complete seasons and 216 episodes, earning a solid 8.2/10 rating that honestly doesn’t capture how deeply this show burrowed into the collective consciousness. This wasn’t just another adaptation; it was a complete reimagining of what a cape-and-tights story could be on television.

The genius of what Alfred Gough and Miles Millar created lies in their fundamental insight: the most interesting Superman story isn’t about the hero in the suit, but about the boy before the suit existed. By anchoring the entire series in the small Kansas town of Smallville, they grounded an inherently fantastical premise in genuine emotional stakes. The show operated in that sweet spot where sci-fi spectacle collided with intimate character drama, using its 43-minute runtime to balance monster-of-the-week procedural beats with serialized mythology that actually mattered.

Here’s what made the show’s approach so revolutionary for its era:

- Treating alien mythology seriously within a grounded, teenage drama framework

- Using “freak of the week” episodic structure while building toward genuine long-form storytelling

- Exploring trauma, identity, and belonging through the lens of a teenager hiding a world-ending secret

- Gradually introducing DC Comics mythology without ever feeling like fan service (at least, not until later seasons)

- Building romantic tension and genuine relationships that evolved across years, not episodes

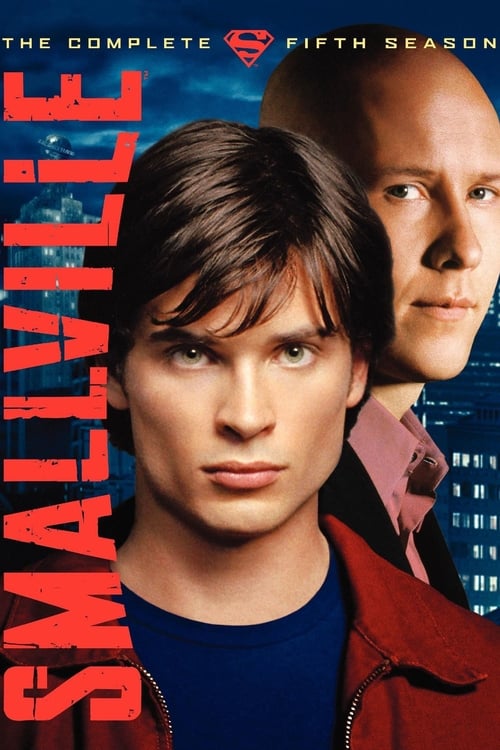

The show’s cultural footprint extended far beyond the devoted fanbase who discovered it through The WB and followed it to The CW. Smallville sparked genuine conversations about what superhero television could accomplish. It arrived at a moment when cape-and-tights properties were treated as inherently juvenile, yet here was a show that didn’t apologize for its source material—it deepened it. The iconic moments accumulated naturally: Clark’s journey from isolated teenager to reluctant hero, the slow-burn romance with Lana Lang that became mythologically complex, the introduction of Lex Luthor as a sympathetic antagonist whose descent into villainy felt genuinely tragic rather than contrived.

The show proved that serialized drama could sustain an audience through ten seasons by making viewers invest in character arcs that actually went somewhere—even when that destination sometimes took risks that divided the fanbase.

What’s particularly fascinating is how Smallville maintained narrative momentum across such a lengthy run. The series evolved significantly across its seasons, constantly introducing new mythology, new threats, and new dimensions to Clark’s abilities and relationships. Early seasons focused on intimate, small-town storytelling with alien-adjacent mysteries. Middle seasons expanded into genuine cosmic threats and the introduction of deeper DC Universe lore. The later seasons became something altogether different—messier, more ambitious, sometimes more frustrating, but never boring.

The creative achievement here deserves serious recognition, particularly in how economically the show worked within television constraints. Each 43-minute episode had to service multiple storylines: the weekly threat, the character relationships, the mythology progression, and the emotional core. Gough and Millar understood that television is about rhythm and pacing—you can’t sustain a ten-season journey without varying your tempo, introducing new elements when energy dips, and most importantly, making your audience genuinely care about whether your protagonist survives the next episode.

The ensemble cast evolved across the show’s run, but the consistent thread was the development of Clark Kent as a character, not as Superman in waiting. Tom Welling’s portrayal captured something essential: the burden of impossible responsibility falling on someone who just wants to be normal. That internal conflict drove everything. Alongside him, supporting characters like Chloe Sullivan, Lex Luthor, Lois Lane, and eventually Oliver Queen created a complex social ecosystem that felt authentic to teenage experience while accommodating increasingly outlandish supernatural elements.

It’s worth acknowledging that Smallville‘s ten-season, 216-episode arc wasn’t uniformly loved—viewership fluctuated, certain seasons divided fans, and the finale proved particularly controversial. Yet that messiness is almost part of its charm. This show swung for the fences consistently, attempted genuinely experimental storytelling at times, and earned its 8.2/10 rating through sheer commitment to character and mythology rather than playing it safe.

Why Smallville deserves your attention now has everything to do with what it accomplished within the constraints of network television serialization. It proved that superhero stories didn’t need billion-dollar budgets and sprawling cinematic universes to matter—they needed genuine investment in character, consistent thematic exploration, and creators willing to let their story evolve organically. The show influenced everything that came after it, from the grounded approach of early Arrow to the mythology-heavy storytelling that became standard in prestige television.

If you’re exploring Smallville today through Hulu, you’re encountering a show that fundamentally changed how television treated its source material. Ten seasons, 216 episodes, and nearly a decade of storytelling later, it remains a fascinating case study in how to sustain an audience’s investment in a single character’s transformation. That’s not just nostalgia talking—that’s television achievement worth examining.