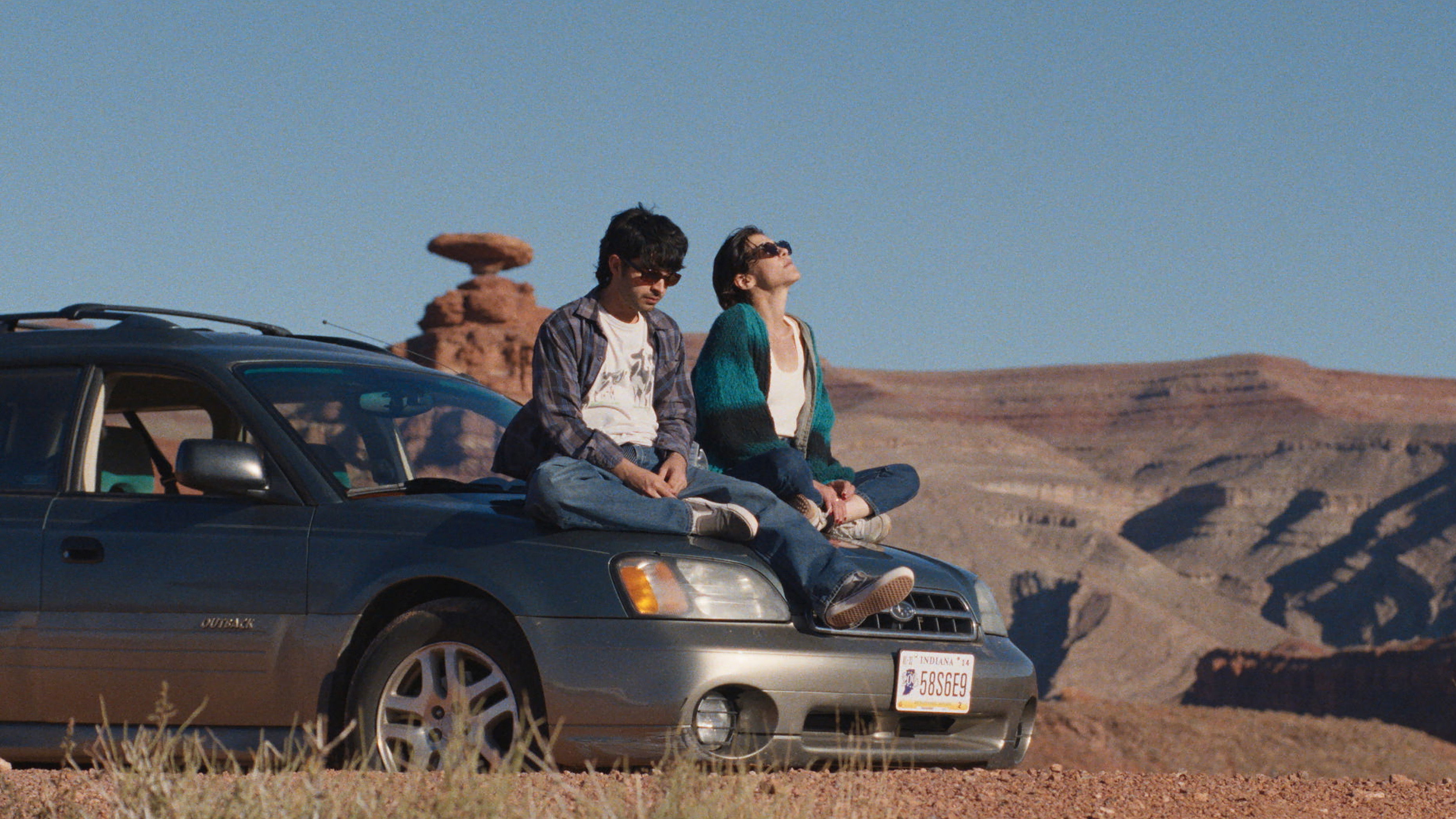

When Hot Water premiered at Sundance in January 2026, it arrived during a particularly poignant moment for the festival—a year dedicated to honoring Robert Redford’s legacy while the independent film world continued grappling with what cinema could do in an increasingly fragmented media landscape. Director Ramzi Bashour brought a lean, focused vision to the competition: a taut 1 hour 37 minute drama that wastes no time getting to the emotional heart of its story. In an era where festival selections can feel bloated or overly ambitious, there’s something refreshingly honest about a filmmaker who trusts their material enough to let it breathe within such a contained frame.

The film’s significance lies not in box office dominance or immediate critical consensus—its financial trajectory remains undisclosed, and it entered the world without a predetermined numerical rating—but rather in what it represents about contemporary independent filmmaking. Lubna Azabal, an actress of considerable depth and international experience, carries the narrative with a presence that suggests quiet complexity beneath the surface. Opposite her, Daniel Zolghadri and Tedd Taskey form an ensemble that Bashour has clearly orchestrated with deliberate care. What makes this collaboration memorable is how economical it feels; with limited runtime and an ensemble approach, there’s no room for indulgence. Every scene had to earn its place.

Bashour’s direction suggests a filmmaker uninterested in easy answers or sentimentality—instead, Hot Water appears concerned with the textures of human conflict and the ways relationships fracture under pressure.

The creative vision at work here speaks to something broader about where independent cinema is heading. Rather than chasing spectacle or narrative complexity for its own sake, Hot Water seems to operate in a more intimate register. The involvement of multiple producers and production companies—Cow Hip Films, Morning Moon Productions, Spark Features, Cinereach, The Sakana Foundation, Liucrative Media, MacPac Entertainment, and Further Adventures—suggests the kind of collaborative, distributed funding model that’s becoming increasingly common in indie film. This isn’t a singular auteur project bankrolled by a single source; it’s a collective effort assembled across different entities, each bringing resources and perspective.

What Hot Water ultimately demonstrates is the enduring power of small-scale, character-driven drama. In a festival season dominated by high-concept documentaries, genre experiments, and prestige adaptations, Bashour’s film carved out space for something more elusive: a story about people in crisis, told with formal restraint. The brevity of its runtime actually becomes an asset rather than a limitation—it forces the narrative to prioritize emotional authenticity over plot mechanics, to trust the audience’s ability to read subtext and silence.

Key elements that define the film’s approach:

- Economical storytelling that privileges character over plot exposition

- A committed ensemble cast working within intimate scale

- A production model that reflects contemporary independent film financing

- Direction that suggests restraint and formal control

- Runtime that enforces narrative discipline

The cultural landscape Hot Water emerged into was one where festival films were increasingly expected to announce their significance loudly—through critical accolades, social media moments, or immediate cultural relevance. Yet some of the most enduring works from any era are those that arrived quietly, trusting their craft rather than their marketing. Bashour seems aware of this. There’s an intelligence in how the film was constructed and presented, a sense that the work itself is sufficient.

The fact that Films Boutique secured international sales rights speaks to how the industry perceived the film’s potential to resonate beyond festival circuits and domestic markets. There’s clearly something in Hot Water that travelled—something that transcends regional specificity or cultural particularity. Whether that’s thematic universality or the quality of performances is partly what makes it worth discussing. The film became part of a 2026 Sundance cohort that critics were already calling transformative, positioned alongside documentaries tackling immigration, explorations of Black culture, and other socially conscious work.

Yet for all its seeming importance within festival infrastructure, Hot Water remains deliberately, almost stubbornly resistant to easy categorization. It’s not a problem-picture in the traditional sense; it doesn’t announce its themes or offer simple resolutions. What it offers instead is presence—the presence of skilled actors navigating emotional terrain, the presence of a director who knows when to cut, when to hold, when to let silence speak.

Why this matters for cinema moving forward:

- It demonstrates that intimate, character-driven work still finds funding and distribution networks in an era of streaming dominance

- It shows how formal restraint can be a creative choice rather than a limitation

- It proves that festival prestige isn’t always about spectacle or immediate critical consensus

- It represents a production model increasingly necessary in independent film

For anyone paying attention to where cinema is heading, Hot Water is a necessary text. Not because it reinvents the medium or makes grand statements, but because it reminds us that cinema remains, fundamentally, about watching human beings navigate complexity. Bashour, Azabal, Zolghadri, Taskey, and the entire production understood that. In an industry that often confuses noise with significance, Hot Water suggests that sometimes the quietest voices carry the most weight.