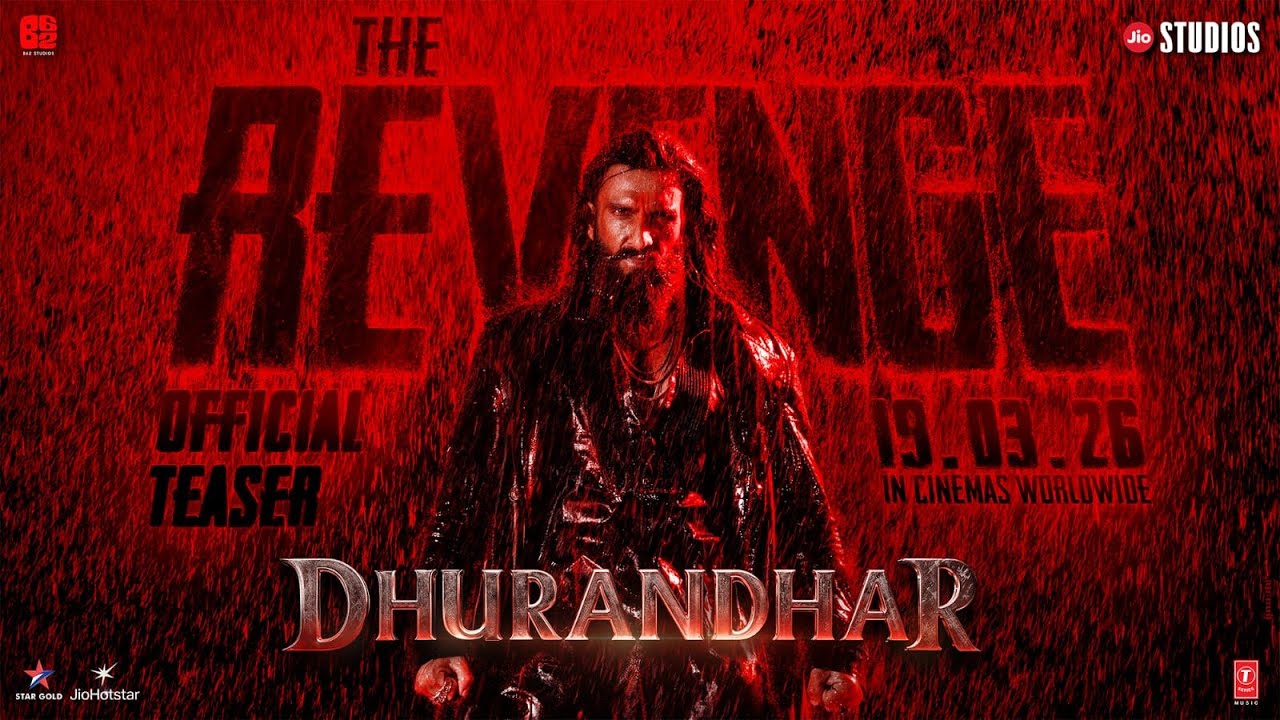

Aditya Dhar is returning to the action-thriller space with Dhurandhar: The Revenge, a sequel to his 2019 film Dhurandhar. The original came to the market as a significant commercial success, establishing itself as a major box office draw in Indian cinema. Now, with this follow-up scheduled for release on 2026-03-19, Dhar is looking to expand on what worked before while deepening the narrative stakes. His filmmaking approach has consistently centered on gritty action sequences grounded in character-driven storytelling, a balance he first proved with the original film’s reception and performance.

What makes Dhar’s work distinctive is his willingness to dig into morally complex territories. The synopsis for The Revenge—where “the line between patriot and monster disappears”—signals that Dhar isn’t interested in simple good-versus-evil narratives. This thematic ambiguity has defined his best work, where action sequences serve the story rather than interrupt it. The three-hour-and-thirty-minute runtime reflects an ambition to give both character development and spectacle adequate space, which is a significant commitment in contemporary Hindi cinema.

The casting here reveals careful thought about who can carry these kinds of roles. Ranveer Singh plays the central character Hamza, a role that demands someone capable of portraying internal conflict. Singh has demonstrated range across multiple genres—from the vulnerability in Padmaavat to the explosive energy in Gully Boy. His track record shows he can anchor films that require physical intensity and emotional nuance simultaneously. Pairing him with R. Madhavan, an actor known for intelligent, grounded performances, adds another layer. Madhavan’s work in films like Rocketry and 3 Idiots shows he brings credibility to complex characters. Then there’s Arjun Rampal, whose antagonistic presence in Om Shanti Om and The Last Hour indicates he understands how to make villains feel like genuine threats rather than cartoonish obstacles.

The relationship between these three actors on screen matters because the synopsis hinges on personal conflict spiraling into larger warfare. Singh against Rampal’s ruthless Major Iqbal, with Madhavan potentially caught somewhere in the moral maze—that’s a dynamic that only works if the actors understand the gravity of what their characters are doing.

Production-wise, this is a significant undertaking. Both Jio Studios and B62 Studios are involved, which represents substantial institutional backing. Jio Studios, in particular, has established itself as a major force in Hindi cinema’s production landscape, willing to invest in ambitious action projects. The first Dhurandhar grossed considerable sums at the box office, and that commercial validation likely played a role in securing resources for a larger, longer sequel. A 3.5-hour runtime isn’t casual filmmaking—it’s a statement of intent about complexity and scope.

The film also exists within a multilingual framework, with versions in Hindi, Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, and Malayalam. This approach reflects how Indian cinema has evolved, where a successful action-thriller can appeal across linguistic and regional boundaries. It’s a practical acknowledgment that films like this now operate in a pan-Indian market rather than a siloed regional one.

The tonal ambition of the narrative is worth examining. The tagline—”Ab Bigadne Ka Waqt Aa Gaya Hai” (Now it’s time to go bad)—suggests a protagonist who’s pushed beyond a moral boundary. This isn’t a story about good guys versus bad guys; it’s about what happens when someone fighting for their country becomes indistinguishable from the criminals and corrupt officials they’re opposing. That’s thematically complex territory, and it requires filmmakers and actors willing to sit with moral ambiguity rather than resolve it neatly.

Hamza’s mission spirals into a bloody personal war where the line between patriot and monster disappears in the streets of Lyari.

Lyari—a neighborhood in Karachi—is a specific, real location. This geographical precision matters. Dhar isn’t working with a generic crime-ridden city; he’s placing his narrative in a particular place with its own history, economy, and social structures. That specificity could make the film feel more grounded than typical action thrillers that exist in abstract spaces.

What this sequel is attempting requires the filmmaking team to understand that bigger isn’t necessarily better. With 3.5 hours to work with, Dhar could easily let action sequences bloat or drag out exposition that doesn’t serve the story. His previous work suggests he understands restraint—that tension comes from what’s withheld as much as what’s shown. Whether he sustains that discipline across an extended runtime will determine whether The Revenge feels like an expansion of the original’s strengths or an indulgent rerun of its formula.

The franchise element here is straightforward: this is a direct sequel to a commercially successful film, and sequels in Hindi cinema have a particular challenge. They need to acknowledge what audiences loved about the original while offering something that justifies a return visit rather than a repeat. The shift from the original’s narrative to this one—from introduction to consequence—suggests Dhar has thought about progression rather than repetition.