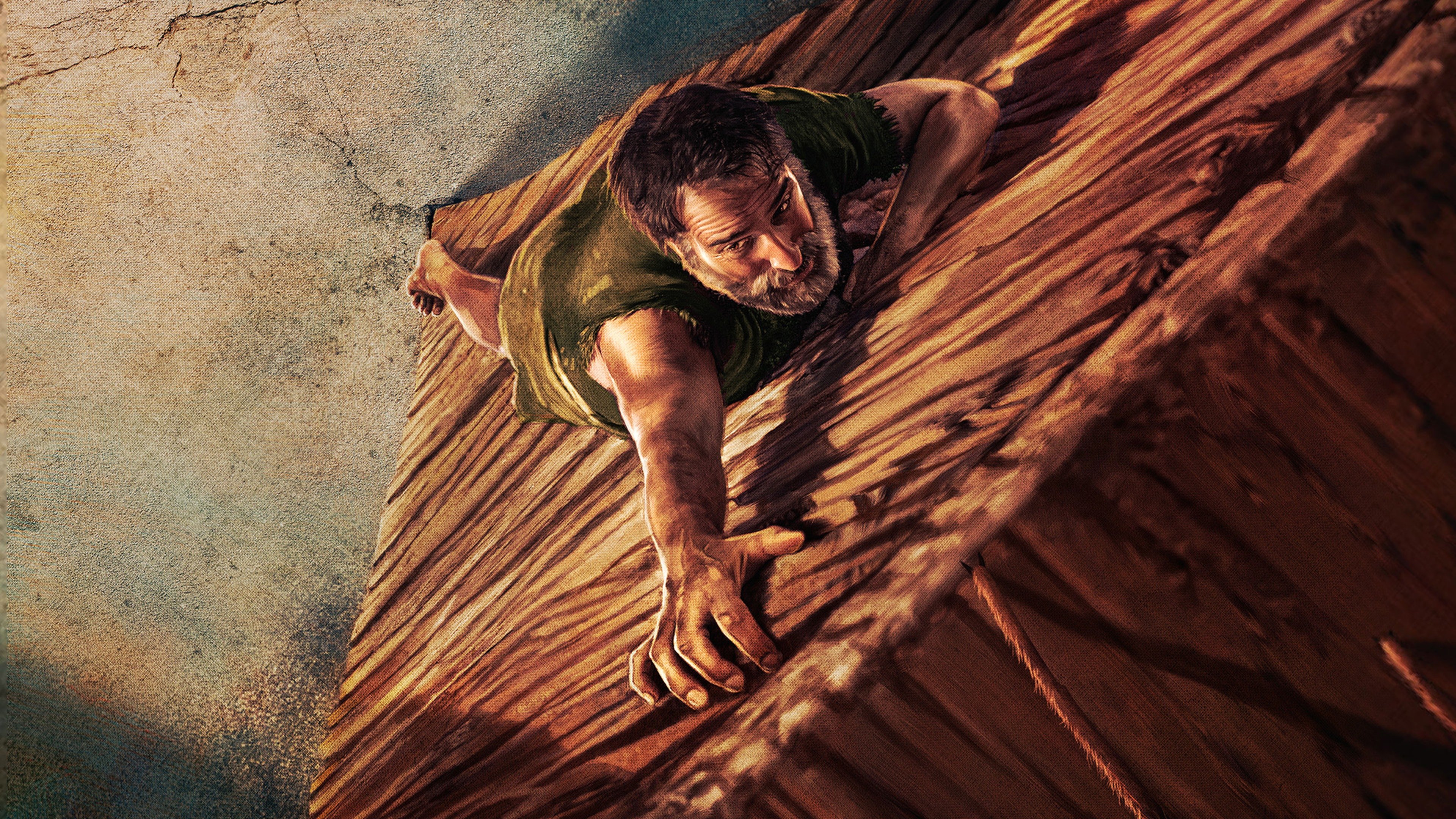

When Jan Kounen’s The Shrinking Man premiered at the Sitges Film Festival in 2025, it arrived as a quiet reinvention of a concept that had been dormant in popular cinema for decades. This French-Belgian co-production, backed by a modest $24,350,000 budget across multiple production houses including Pitchipoï Productions and TF1 Films Production, takes the existential terror of bodily transformation and grounds it in something almost claustrophobically intimate: a man losing his place in the world, literally and figuratively, within the confines of his own home.

The premise itself is deceptively simple. A shipbuilder inexplicably begins to shrink, eventually finding himself trapped in his basement measuring only inches tall. What could have been a straightforward sci-fi spectacle instead becomes a meditation on powerlessness and the grotesque inversion of domestic space. Kounen understands that the real horror isn’t the shrinking—it’s what comes after. When your house becomes a labyrinth and a household object becomes an insurmountable obstacle, the world stops being your home and becomes your prison.

> The film’s true achievement lies not in its special effects or narrative spectacle, but in its willingness to sit with discomfort and claustrophobia for its economical 1 hour 39 minute runtime.

Jean Dujardin carries the film with a performance that oscillates between desperation and grim determination. Known for his charisma in lighter fare, Dujardin strips that away here, channeling a kind of primal survival instinct that feels earned rather than performed. He’s not playing a hero overcoming adversity through wit or charm—he’s playing a man confronting the absolute degradation of everything he took for granted. Alongside him, Marie-Josée Croze and Daphné Richard create a supporting ecosystem that never quite becomes the safety net Dujardin’s character desperately needs. Their performances anchor the film’s emotional reality; this isn’t a fantastical romp, it’s a household tragedy playing out in miniature.

The critical reception hovering around 6.1/10 from early voting suggests audiences found themselves genuinely unsure what to make of the film. That ambivalence might be the truest indicator of its cultural significance. The Shrinking Man doesn’t offer easy catharsis or traditional genre satisfaction. It asks uncomfortable questions about masculinity, agency, and the illusion of control that most mainstream films politely avoid. The box office performance remains unknown, which in itself tells a story—this is a film that likely found its audience through festival circuits and word-of-mouth rather than mass marketing machinery.

What makes Kounen’s vision particularly interesting is how he leverages the production’s international heritage. A collaboration between French, Belgian, and Luxembourg-based companies, The Shrinking Man carries a distinctly European sensibility: there’s an appetite for ambiguity, for visual storytelling over exposition, for letting audiences sit in psychological discomfort. This isn’t the kind of project that emerges from major studio systems, and that creative independence shows in nearly every frame.

The film’s place in science fiction cinema is worth considering carefully:

- It represents a return to intimate, character-driven sci-fi rather than spectacle-driven narratives

- It resurrects source material with genuine respect for its existential core

- It positions bodily horror not as Gore but as philosophical inquiry

- It demonstrates that visual transformation narratives can explore class anxiety and masculine crisis

The shrinking itself becomes a metaphor with extraordinary elasticity. You can read it as commentary on economic precarity, on masculinity in crisis, on the dehumanizing effect of modern life, or simply as pure survival horror. Kounen trusts his audience enough not to point out which reading is “correct”—they all are, simultaneously.

Looking forward, The Shrinking Man will likely influence the next generation of European sci-fi filmmakers who are hungry for an alternative to both bloated American spectacle and the limitations of microbudget genre filmmaking. It proves there’s space in the market for intellectually ambitious, formally inventive science fiction that doesn’t need superhero franchises or streaming platform billions to justify its existence. The film emerged from a specific moment—October 2025, a festival season where audiences and critics were ready for something that felt genuinely strange and uncompromising.

What endures about this film is its refusal to comfort us. There’s no triumphant escape scene waiting in the wings, no clever technological solution to reverse the transformation. What we get instead is a man diminishing in a world that suddenly towers over him, and the steady accumulation of small moments—each one a kind of death—that constitute his psychological unraveling. That’s the legacy Jan Kounen has created here: a film that understands that sometimes the most profound science fiction comes not from asking “what if this technology existed?” but from asking “what if the world you knew became fundamentally, irreversibly hostile?”