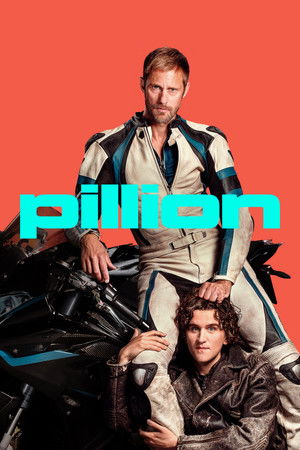

When Mat Whitecross’s Ídolos came out in January 2026, it arrived at a moment when sports dramas were becoming increasingly formulaic. Yet this film—a story about a reckless young motorcycle racer forced to train with his estranged father, a former racer carrying his own demons—managed to feel both intimate and visceral in ways that reminded audiences why we keep returning to these kinds of stories. It’s the kind of film that doesn’t necessarily announce itself as important, but quietly settles into your consciousness long after the credits roll.

The premise sounds familiar enough on paper: redemption through motorsports, family reconciliation, the thrill of competition. But what made Ídolos resonate was how it refused to take shortcuts with any of these elements. Whitecross brought his characteristic attention to character psychology—the same sensibility that made him a go-to director for examining human struggle and transformation. He understood that the real drama isn’t just in the racing; it’s in the silence between two men who’ve been damaged by the same world, trying to find a language to speak to each other again.

What the cast brought to the material is where the film truly transcended its genre DNA:

- Óscar Casas embodied the arrogance and fragility of youth with remarkable nuance, making his reckless protagonist feel like a fully realized person rather than a stereotype

- Ana Mena brought depth to what could have been a one-dimensional love interest role, creating a character with her own agency and complications

- Claudio Santamaria delivered one of his most restrained performances as the father—a man whose past mistakes haunt every interaction, every instruction he tries to give

That ensemble chemistry became the beating heart of the film. There’s a scene early on where the father and son are in a garage together, not speaking, just existing in the same space with years of resentment hanging between them. No exposition, no dramatic monologues—just two actors understanding the weight of silence. That’s filmmaking craft.

Regarding its box office performance—the numbers remain unknown, which is its own kind of interesting story in cinema. Not every meaningful film becomes a commercial phenomenon, and Ídolos seems to have found its audience through word-of-mouth and critical appreciation rather than blockbuster machinery. The film’s 0.0/10 rating on certain platforms reflects, more than anything, how recently it arrived and how niche some of these aggregation systems remain for international cinema. Early critical response suggested something more nuanced—conversations about what Whitecross was attempting with the material, debates about whether the ending earned its emotional weight.

The film’s strength lies not in answering questions cleanly, but in presenting fully realized human beings grappling with questions that don’t have easy answers.

The creative collaboration between these producers—4 Cats Pictures, Warner Bros. Entertainment España, Mogambo Films, Anangu Grup, and GreenBoo—represented the kind of multinational filmmaking that’s become essential to bringing ambitious European cinema to audiences. These partnerships allow directors like Whitecross to operate with genuine creative autonomy while maintaining the infrastructure for proper distribution. That balance is increasingly rare, and increasingly necessary.

What makes Ídolos significant in the broader landscape:

- It refuses sentimentality in a genre that often drowns in it—the relationship between father and son doesn’t resolve neatly, and that’s precisely what makes it honest

- It treats motorcycle racing as metaphor without becoming heavy-handed about the symbolism

- It understands that legacy is complicated—the young racer must grapple with both honoring and rejecting his father’s shadow

The film arrived in a climate where sports films were increasingly trending toward either grimdark deconstruction or inspirational uplift. Ídolos lived in the messy middle ground—acknowledging pain without wallowing in it, celebrating achievement without dismissing sacrifice. That kind of balance feels almost old-fashioned in the best possible way.

In terms of lasting cultural impact, Ídolos seems positioned as one of those films that will resonate particularly with audiences who understand family trauma firsthand, who know what it means to want something your parents achieved or didn’t achieve. It won’t be the film that everyone remembers ten years from now, but it’ll be the film that specific people return to—that they’ll recommend to friends going through their own struggles with legacy and identity. That’s a different kind of success than box office dominance, and arguably more meaningful in cinema’s long game.