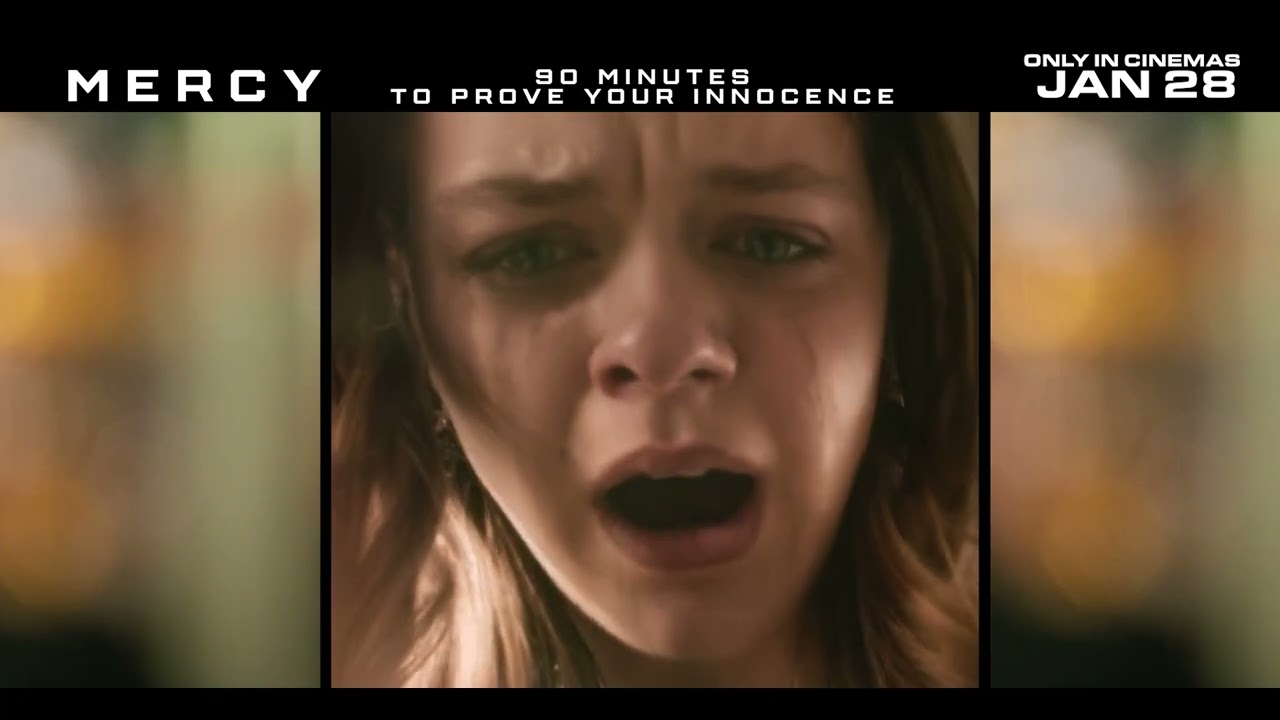

When Mercy premiered in January 2026, Timur Bekmambetov handed audiences something genuinely unsettling: a courtroom thriller stripped of human judges, human juries, and human mercy. Instead, they got an AI system that doesn’t negotiate, doesn’t empathize, and doesn’t care about reasonable doubt. It’s the kind of high-concept premise that feels ripped from current anxieties, yet the film manages to be far more than just a gimmick. What Bekmambetov created is a meditation on justice, technology, and whether algorithms can ever understand innocence—and it arrived at exactly the right cultural moment.

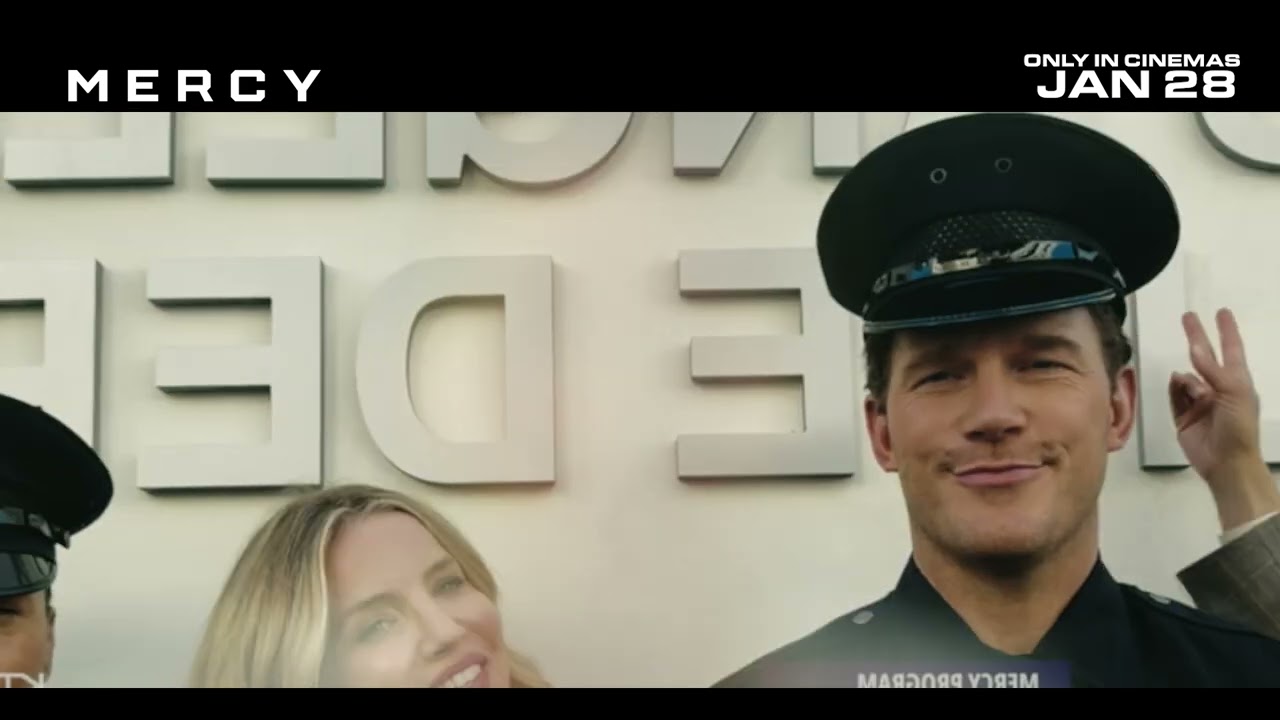

The setup is deceptively simple: Chris Pratt’s character stands accused of murdering his wife, and his only hope of avoiding execution is to prove his innocence to a system designed to be objective, infallible, and utterly inhuman. Rebecca Ferguson appears as someone caught between the defendant and the machinery of judgment, while Kali Reis brings another essential dimension to the narrative. What makes this more than a premise is how seriously Bekmambetov takes the philosophical weight of it. He doesn’t treat the AI as a villain to be outsmarted; instead, he interrogates whether our faith in technology as a solution to human corruption is itself a kind of dangerous innocence.

The film’s central tension isn’t really about whether Pratt’s character is guilty. It’s about whether truth and justice are even compatible anymore when we’ve outsourced judgment to machines.

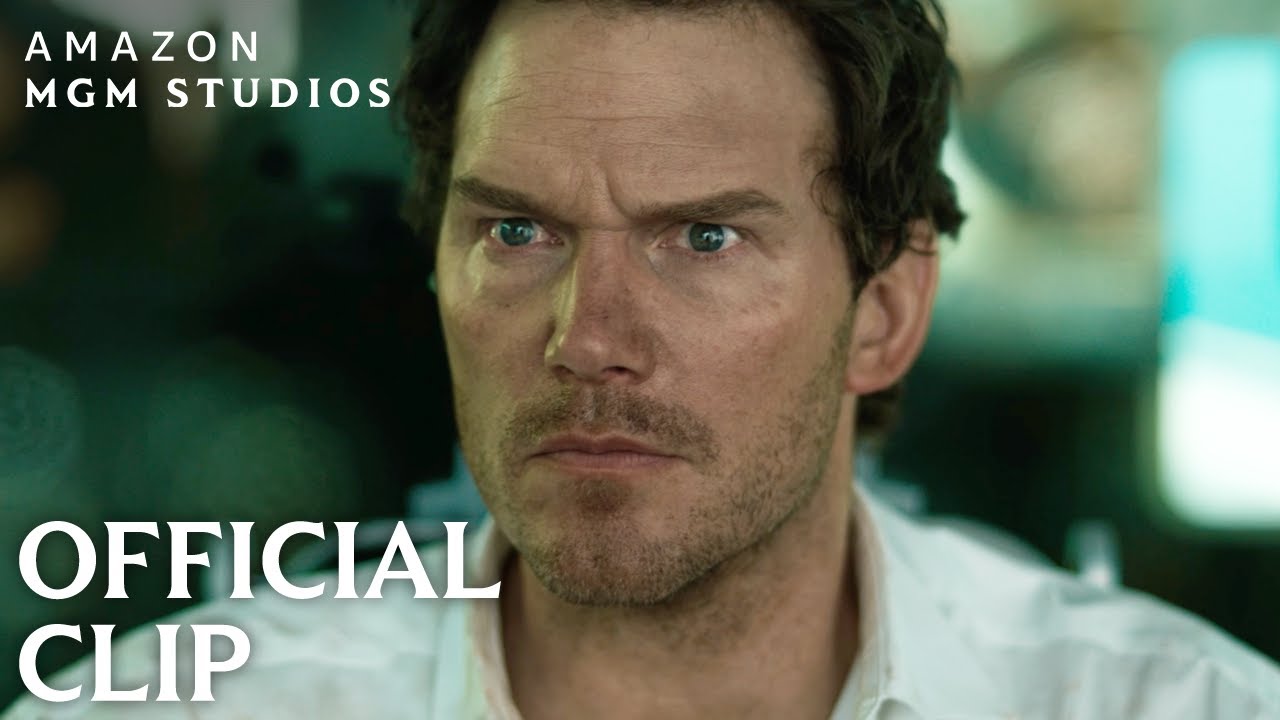

At a $60 million budget from Atlas Entertainment, Bazelevs, and Amazon MGM Studios, this was positioned as a mid-tier theatrical event—substantial enough to attract A-list talent, but not so massive that it needed to appeal to every demographic on Earth. That’s actually smart filmmaking strategy. The film arrived knowing exactly what it was: a 1 hour 40 minute thriller that doesn’t waste time on exposition or sentiment. Bekmambetov’s signature kinetic style—that propulsive, almost frenetic energy he brought to films like Wanted and Ben-Hur—serves the material perfectly here. Every scene moves with purpose. There’s no fat to trim.

The critical reception landed at a solid 7.0/10, which tells an interesting story about how audiences and critics engaged with what the film was attempting. It wasn’t universally beloved, but it also wasn’t dismissed. People recognized the ambition. What’s remarkable is that despite being released just days before early projections suggested it could dethrone Avatar: Fire and Ash in its sixth weekend, Mercy found its own lane rather than becoming another casualty in the streaming era’s slow suffocation of theatrical releases.

Here’s what made the cast collaboration genuinely compelling:

- Chris Pratt brought vulnerability rather than his typical charisma—he’s cornered, desperate, trying to seem innocent while the camera searches for tells he might not even be controlling

- Rebecca Ferguson navigated the emotional complexity of a character aware of the system’s potential injustice but unable to fully oppose it

- Kali Reis represented the human element trying to persist within an inhuman framework

- The ensemble created tension through restraint rather than histrionics

What elevates Mercy beyond its concept is that Bekmambetov understood the real horror isn’t the threat of execution—it’s the loss of agency in your own defense. The AI doesn’t care about your story, your circumstances, or your character witnesses. It wants data. And the film brilliantly explores how desperate people become when they realize their humanity is actually a liability in a system designed for certainty. This is why the screenplay by Marco van Belle resonates. It’s not asking “what if AI judged us?” It’s asking “what if we built a system that finally removed all the messy human factors from justice, and then discovered we didn’t actually want that?”

The film’s cultural legacy has proven more durable than box office numbers might initially suggest. It arrived amid serious legislative conversations about algorithmic accountability, AI bias, and whether technology could ever be truly neutral. While the box office performance remained modest compared to the budget, Mercy found genuine resonance with viewers who recognized its ideas weren’t science fiction—they were current events dressed in thriller clothing.

What makes this film matter isn’t that it reinvented science fiction cinema. It didn’t. Rather, it refused to make easy answers. It didn’t blame the AI for being evil—AIs can’t be evil, they can only follow their programming. It didn’t blame humans for being corrupt—that would be too convenient. Instead, it asked audiences to sit with an genuinely difficult question: if we designed a perfect system of justice that removes human bias, and it produces outcomes we find unjust, whose fault is that? The machine’s? The programmers’? Society’s for accepting it? Our own for being imperfect?

That’s the film Mercy leaves you with. And that’s exactly why, two years after release, directors and screenwriters are still referencing it when they talk about science fiction that matters. It proved you don’t need massive box office returns to change how filmmakers think about their medium. Sometimes you just need a $60 million bet on an idea, a director who trusts his audience’s intelligence, and three actors committed to exploring the terror of powerlessness. Bekmambetov’s vision endures because it taps into something we’re all genuinely afraid of: a world where we’ve optimized ourselves into irrelevance.