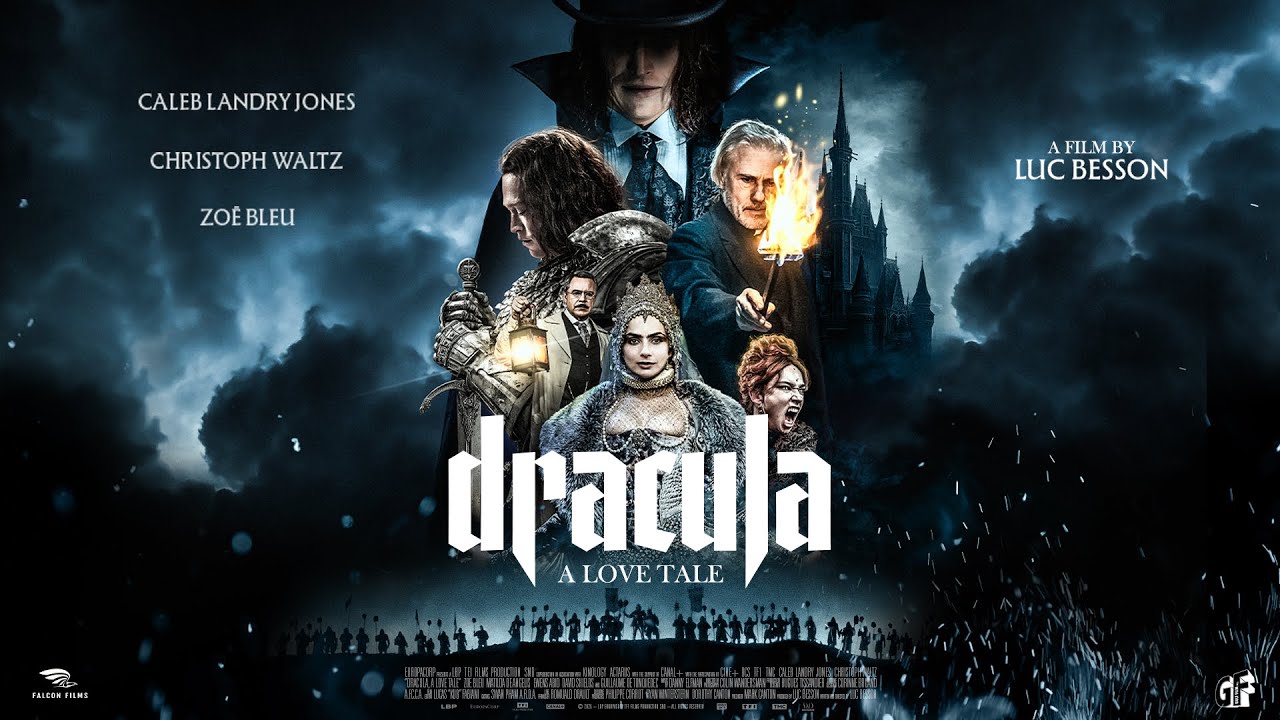

When Dracula arrived in theaters last summer, it came with the weight of expectation that only a Luc Besson production can carry. Here was one of Europe’s most prolific and visionary filmmakers taking on cinema’s most iconic monster—not with reverence for the source material, but with a distinctly modern sensibility.

The result was a film that didn’t quite become the cultural phenomenon the $52 million budget suggested it might be, yet it arrived at something perhaps more interesting: a genuinely divisive, intellectually ambitious take on immortality, faith, and what it means to renounce your humanity for power.

Let’s talk about the numbers first, because they tell a story worth understanding. The film earned $28.6 million globally against its substantial production budget—a shortfall that would typically spell commercial failure. Yet that narrative misses what actually happened. Dracula became France’s third-largest export film of 2025, sitting comfortably behind the phenomenon of Flow but proving that Besson’s vision found an international audience willing to meet it halfway.

The film wasn’t a tentpole blockbuster, but it was never meant to be. What matters is that audiences showed up, stayed for the full 2 hours and 10 minutes, and walked away either energized or provoked—and honestly, for a gothic horror-romance, that’s the goal.

“He renounced his faith to become immortal. Passion, anger, vengeance, and hatred will be unleashed into the modern world.”

The tagline cuts to the film’s actual thesis, and this is where Besson’s vision becomes genuinely clever. This isn’t Bram Stoker through a 19th-century lens, and it’s not the gothic melodrama audiences might expect.

Besson brought several crucial elements to this adaptation that set it apart from the crowded vampire canon:

- A contemporary sensibility applied to an ancient myth—treating immortality as existential curse rather than romantic fantasy

- Visual spectacle that uses the production’s considerable budget to create distinctive set pieces, not just gore

- A focus on theological doubt as the emotional core, rather than pure horror mechanics

- Casting choices that prioritized distinctive performances over conventional star power

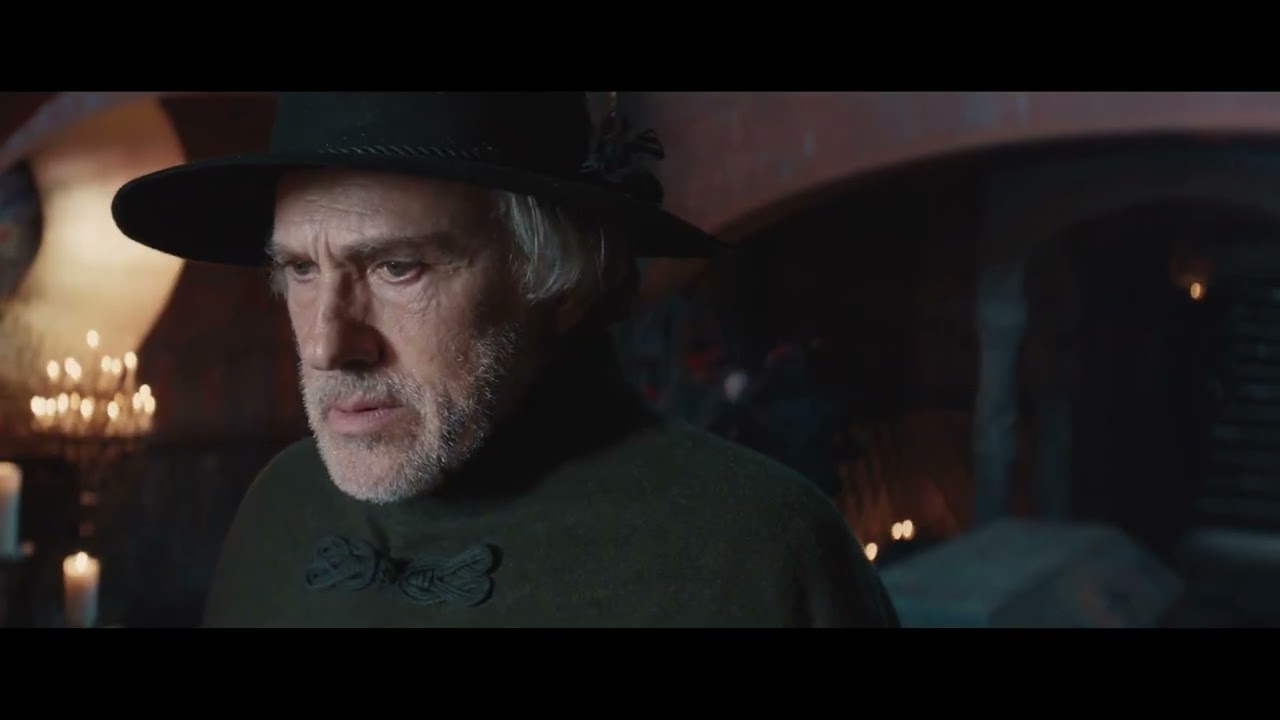

Caleb Landry Jones carries the entire film as Dracula, and this was perhaps the most crucial decision Besson made. Jones isn’t a traditional leading man—he’s an actor known for unsettling intensity and emotional depth. His Dracula is neither seductive nor purely monstrous. Instead, Jones constructs a character of profound, almost philosophical anguish. You watch him wrestle with centuries of regret, with the bargain he struck when he rejected his faith. It’s a performance that demands patience from viewers, and while the 7.2/10 rating suggests mixed reactions, that polarization often signals an actor taking real risks.

Christoph Waltz, meanwhile, emerges as the film’s moral anchor. Waltz has perfected the art of playing characters who speak with chilling precision about terrible things, and here he uses that gift to ground the narrative in something resembling consequence. Zoë Bleu Sidel rounds out the core triangle, bringing a vitality that contrasts sharply with Dracula’s exhaustion. Their chemistry doesn’t operate on conventional movie-romance wavelengths—it’s stranger, more textured, built on the collision of someone alive with someone who stopped living centuries ago.

What’s fascinating about Dracula‘s cultural moment is how it arrived amid a glut of vampire content yet managed to feel different. The horror genre, broadly, has been consolidating around specific aesthetics and storytelling approaches. Besson’s film instead asks: what if we treated this legend as literature rather than spectacle?

The film’s place in the broader vampire canon reveals itself through what Besson deliberately doesn’t do:

- Reject seduction as the primary vampire trait — Instead, this Dracula is repulsive partly because he’s honest about his nature

- Avoid the religious dimensions of the myth — The faith element isn’t set dressing; it’s the narrative spine

- Sidestep contemporary setting complications — Modern world intrusion forces all characters to reckon with immortality in 2025 terms

- Lean on gore as substitute for philosophy — Violence serves the emotional argument, not the other way around

The box office disappointment, then, reads less like failure and more like a film that found its audience but didn’t find the mass audience. That’s not pejorative. Many of cinema’s most enduring works faced initial commercial resistance. The question is whether Dracula has the staying power to become one of them, and early indicators suggest it might.

The film’s recognition at international festivals, its performance as a French export, and its gathering critical reassessment all point toward a work gaining appreciation rather than losing it. The 754 votes informing that 7.2 rating suggest a specific, engaged audience rather than a wide casual viewership—which means the conversation around this film is likely deepening rather than fading.

Besson proved he could still command massive resources while asking genuinely difficult questions about faith, immortality, and the cost of power across centuries.

What Dracula represents, ultimately, is European cinema still reaching for mythic scope without surrendering artistic ambition. In an age where most vampire films either commit to Gothic pastiche or contemporary action, Besson’s film attempts something harder: to make immortality feel like a genuine tragedy. It doesn’t always succeed—the 2 hour 10 minute runtime occasionally strains against the narrative’s philosophical weight—but the ambition matters. The film failed commercially in traditional terms, yet it succeeded culturally in finding an international audience, influencing the conversation about how classic mythology functions in contemporary horror, and proving that there’s still a place for intelligent, visually sophisticated takes on worn material.

That’s legacy enough.